The date is February 11, 2014. Log entry: first radiation treatment. I’m scared as heck because I have no idea of what to expect, other than some side effects and having to wear that confining mask.

We started off by checking in at radiation reception. The receptionist handed me a schedule that listed all of the radiation appointments lined up for me for that week, then she showed me how to check myself in at a computer kiosk so that they would know I had arrived each day. She instructed me to check back in with her each Tuesday morning to get the next round of appointments.

As we took our seats in the waiting room, the first thing that struck me was just how many people there were, all waiting for treatment. There weren’t any kids, other than those accompanying a cancer patient. I suppose that any children with cancer would be treated at Sick Kid’s instead. I think it would have broken my heart to see young cancer patients. As it was, it was difficult not to feel pity or heartbreak for some patients. Some were in a very bad way and their suffering was obvious, whereas my cancer was hidden and I showed no outward symptoms.

The waiting room itself was large, bright and airy, with large windows at one end that looked out into the gardens. It was winter so there wasn’t much to see, but I imagined that it would be daffodil-covered come spring time. Magazines and novels were everywhere along with brochures for home health care, nursing homes, and the like. There were tables set up where one could attempt to piece together one of the many donated picture puzzles. Baskets of yarn and knitting needles were placed on all of the coffee tables so that idle hands would have something to do while waiting. A free coffee station was set up at one end. The offices for the dietician, social worker, and Canadian Cancer Society were just off to the side, along with a Druxy’s deli. Volunteers paced the waiting room tidying up books, refreshing the supplies at the coffee station, or helping those who needed it.

When my name was called I expected to be taken to my treatment, but instead we were greeted by a radiation therapist who guided us to a small orientation room. He proceeded to explain how the radiation works and the procedure I would undergo. He explained how they determine where to radiate based on years and years of the collected results from many other cancer centres and cancer research, and that my treatment is based on known, good practices. He also explained how radiation therapy works. It’s not a solid beam as one might think, it’s more like falling raindrops. He said that the radiation doesn’t actually kill the cancer cell; instead, it kills the ability of the cell to reproduce. The cancer cell lives on but it can’t grow, and eventually it will die off. This is why tumours don’t shrink immediately.

I was told that I should make every attempt to attend each treatment and not to skip any. This would give me the best chance of beating cancer. Each session would last about 45 minutes, including prep time to get me on the bed and in position.

We were then led to my assigned radiation unit, lucky number 07.

I changed into my hospital gowns: one with the opening at the back so that the shoulders could be bared for the mask, and another one over top of that with the opening at the front, like a housecoat. Everything had to be removed from the waist up. Again I took a seat to wait my turn.

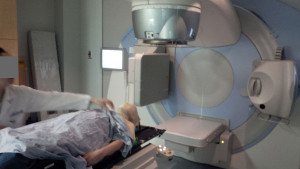

Finally I was called in. The radiation therapists (there were three) led me to the room where I got my first glimpse of the radiation unit. It was large and had a skinny bed, just like the one they used for preplanning. They confirmed my identity by asking for my name and birthdate. I was instructed to always give them my birthdate even if they don’t ask for it. It was to ensure that I was the correct patient who would be receiving the radiation treatment that was programmed into the computer and ready to run specifically for me.

They asked me to remove my housecoat and glasses, untie my gown, and lie on the bed, just as I’d done in preplanning. I soon learned that modesty had to be left at the door because my “lady parts” would be partially on display in front of men as well as women. They needed to pull the gown down so that they could find the tattoo given to me during preplanning. Once they found it and I was lined up, they’d pull the gown up again to cover me. My shoulders would be left bare (and cold) in order to accommodate the mask which they put on me, then they clamped it down. I was immobilized again.

In the pictures above you can see the green laser beam that was used to line me up correctly and precisely every treatment. The round section of the radiation unit behind my head revolved around the bed to project the radiation from different angles during treatment. If you wish you can click on the images to see a larger view of them (you can actually see what’s written on the close-up of the mask). The radiation therapist’s face has been hidden for privacy protection. My husband Seaghan was kindly allowed into the room to take these photos on my birthday, which was exactly one week before the end of treatment. It was the first and only time he’d be permitted to see me like this.

The radiation therapists then explained that I would be the only one in the room during the treatment since radiation was being used. They would be monitoring me from another lead-lined room nearby via closed-circuit TV. I could cough if I needed to as long as I didn’t move; however, if something was wrong such as I was going to be sick, I should raise my hand and they’d stop treatment immediately. The bed was slid into position and they left. A warning alarm was sounded, and the door was sealed shut. It seemed like eons for the door to automatically close completely and all I could think of was “please dear God, don’t let there be a fire — the door couldn’t possibly open fast enough to save me”.

Once the door closed, the therapists spoke to me via intercom to ask if I was OK. I gave a thumbs up (the mask not only immobilized me, it also muzzled me). I could hear the machine starting to work and I tensed up, not knowing what it would be like.

I shouldn’t have been worried. It’s just a big X-ray, only for a longer duration and with moving parts. There’s no pain, no sense of anything happening at all other than the noises the unit made. Great, only 30 minutes to go now.

I could hear two distinct sounds: the first sounded like gears engaging, followed by a high whiney sound. Then came the gear sound again, then the whiney sound again. Over and over again. After a little while I grew brave enough to try to open my eyes, and I found that I was able to open them just enough to see what was making those sounds. The mechanism inside the head of the radiation unit was just above my head at some points during the treatment (don’t forget that it rotates around the bed), and I was able to watch it changing shape.

You see, radiation beams are actually shaped to the tumour itself, targeting the tumour from different angles, in order to minimize impact to the surrounding healthy tissue. It was fascinating to watch (I was a captive audience.) It reminded me of shifting piano keys and at one point I saw the boot shape of Italy. In subsequent treatments I would come to realize that seeing the boot meant I was nearly done that day’s treatment. The gear sounds accompanied the shape changes, and the whine was the actual radiation treatment. The beam was reshaped and/or repositioned 78 times during each session (yes I counted it, what else was there to do?) My bed was turned 90° for last few minutes to get radiation from a perpendicular angle.

At least I didn’t have to look at boring plain ceiling tiles while I was immobilized. In my treatment room I was able to enjoy a nice painting of sunflowers that a volunteer had painted on a ceiling tile, courtesy of Sunnybrook’s ceiling tile project. The radio was playing in the background, tuned to Toronto’s CHFI, so I had music and familiar voices to listen to, and the lights were dimmed just a wee bit (or did it just seem that way because of the mask??) It helped me take my mind off of where I was, at least a little bit, to keep claustrophobia at bay.

When the session was done I was released, but not before being told to use lanolin-free moisturizing cream, such as Glaxal Base, on the skin where I had been radiated. This would help moisten the skin and provide relief from the radiation burn which would become more apparent in future sessions. I felt no after-effects after my first session.

I would become very familiar with radiation unit 07. I would be glued to it five days a week Monday to Friday, forty-five minutes a session, for seven weeks. There would be no treatment on the weekends in order to allow the healthy tissue to recover somewhat. Take away two stat holidays during that time, and that totals thirty-three sessions in all. It didn’t all go as smoothly as the first session, but that’s another story for another time.

—Sandi

Next: getting my feeding tube

Another interesting read….the description of the radiation beam is fascinating…I also wondered how you didn’t go stir crazy bolted down.

Hi Little Sis! I’m lucky in that I don’t typically experience claustrophobia, but it helped me to relax by pretending that I was just going to have a little nap on the bed. The music in the background helped, and in later sessions when fatigue was settling in I was just glad to lie down and I didn’t care what they did at that point.

I also heard that a mild sedative may be prescribed by a medical professional for children to lessen their anxiety. It’s worth checking into for adult patients who might experience anxiety or claustrophobia.

Lucky no. 7; that is also MY lucky number, too, and it proved itself worthy 🙂 Go figure!